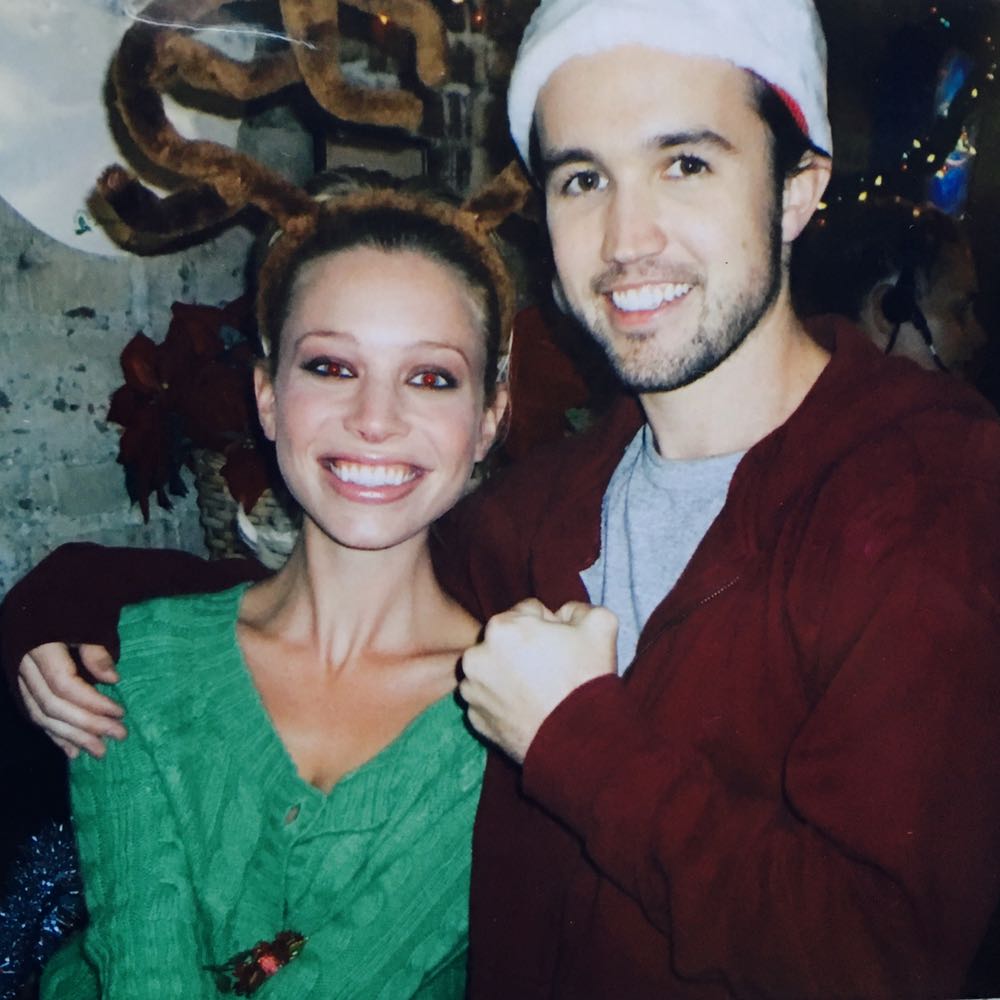

{ New Mexico road trip with my then-boyfriend Jason | 2005 }

For about four years in my mid-twenties (roughly ages 22 to 26), I was anorexic.

Just typing out that sentence is a big deal for me, because for a long, long time it wasn’t something I admitted even to myself, and certainly not to anyone else. I’ve always referred to it as “that time when I was super fucked-up” or “that time when I decided not to eat ever again” – jokey, hyperbolic half-truths intended to swing the conversation towards lighter subjects. I’ve never even said the word “anorexia” to my mother; I called her yesterday to talk to her about this post so she wouldn’t be blindsided (although of course she knew anyway). But over the past few weeks, I’ve found myself saying out loud to one friend or another, whenever a related subject comes up, “Oh yeah, I was anorexic.” And we talk about it or we don’t, but it’s out there either way.

I’ve been trying to figure out what changed; what made me start feeling like that was a thing that I could – even should – say. For a long time the thought of laying that boulder of a title on my shoulders was beyond comprehension: sort of like “I have a mental disorder,” it’s the kind of thing that once you say, you can’t take back. But now I don’t care who knows this about me, just like I don’t care who knows that I have an ugly tattoo on my lower back or that I take Zoloft to control my anxiety or that sometimes I put my children in front of the TV because it’s 6PM and I’m done with the whole “parenting” thing for the day. All facts; all things people might take issue with; all things I’m cool with saying out loud.

So what happened? I think maybe I realized that the reason I was so uncomfortable admitting that I was anorexic was far too closely tied to the reason it happened in the first place: I wanted to pretend everything was great. Perfect, even.

Oh man, am I ever not perfect – a fact that I’ve covered in this very space ad infinitum, to the point where it’s sort of funny to me now that I was ever interested in even pretending. In addition to all the stuff that makes everyone imperfect (being a human being, essentially), I have (treated, thank god) anxiety disorder, and severe, crippling (and also treated, also thank god) insomnia. And yeah, I was anorexic. I did drugs when I could find them to make it easier to not eat (and in early 2000s Hollywood finding hard drugs was about as difficult as finding someone who was “writing a screenplay”). But I really didn’t have to, because the rush that I got from watching the number on the scale slip down was all the high I needed.

* * *

It started a couple of weeks after we taped the first episode of It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia (one of the two self-shot episodes we used to sell the series to FX). I remember I was watching back the tape with the guys, and they were laughing about how massive my breasts looked in a scene we’d shot in my apartment building’s basement gym – we’d snuck in our cameras hoping we could film without anyone noticing and/or evicting me. (The episode was actually called “Big-Breasted Violence,” and the scene had been specifically tailored to emphasize my not-inconsiderable cup size…I guess because it was “funny”? I never really did get that joke.) I stared at myself on the screen, and suddenly everything on me looked massive – certainly in comparison to the other actresses who were in the episode with me. I had never been one to weigh myself, but the next day I did, and discovered that I was fifteen pounds heavier than I’d thought.

And so I stopped eating, just like that. I bought a scale, put it in my bathroom, and watched the numbers go down. I developed weird, obsessive habits around my meals, like not eating anything all morning and then, at 11:30AM on the dot, driving somewhere to buy a single slice of pizza with olives, or a Coffee Bean Morning Muffin, or a Coldstone sugar-free sweet-cream ice cream. I’d sit in my car with the seat pushed back as far as it could go and eat my little “meal” as slowly as possible. I lied to people: “Oh, I just ate; I’m so stuffed I couldn’t possibly eat any more,” that kind of thing.

{ On Set | Downtown Los Angeles | 2004 }

At first, I got nothing but pure validation. By the time we shot the actual Sunny pilot commissioned by FX (pictured above) the same actress who I’d felt embarrassed to stand next to was joking about how I made her feel fat. Seemingly overnight, my agents started sending me out for leading-lady roles instead of best-friend ones (you’ve heard actresses refer to this phenomenon countless times, I’m sure; it is real, and it is immediate and obvious and a majorly self-perpetuating cycle). I felt “hot” – not just “pretty,” but actually hot – for the first time in my life.

After awhile, I stopped menstruating – it would be nearly a year before my period came back; a fact that I did an excellent job at ignoring – and started losing my hair. All of a sudden I could see people looking at me a little differently, a little warily. At the gym one day, a trainer stopped me and asked if he could measure my body fat. It was 6%. He told me that it was lower than a professional male athlete’s should be, and that it was dangerous. I left the gym feeling proud, and wishing there was someone I could brag to about my accomplishment.

* * *

Now, with a full decade of hindsight, I know what was going on, of course. I went from being a person who had spent the bulk of her lifetime accomplishing a lot on a daily basis – tangible accomplishments like getting a good grade or writing a paper I was proud of – to being someone who didn’t feel like she was accomplishing anything at all. The title I identified with shifted from “Harvard student” to “struggling actress,” and the reactions I got from others shifted accordingly. I went on auditions, didn’t get the parts, went home to watch Elimidate, and then did it again the next day, and the day after that. I got fired from the job that I had thought would be the turning point in my career. I couldn’t land any roles; couldn’t make my new (and terrible) relationship work; couldn’t figure out how in the world to be happy. But losing weight? That I could do.

I wish I had some astounding nugget of wisdom to share about how, exactly, this turned around, because it did. Shortly after I fled Los Angeles, I quit my pack-a-day smoking habit simply because one day it just didn’t feel especially good anymore and I stopped wanting to hold a cigarette in my hand. I started eating again in much the same way: it started feeling bad to not-eat, and good to eat. I distinctly remember feeling bored with myself; I was so sick of thinking about food, of doing the mental gymnastics required to calculate the calories ingested over the course of any given day.

I know that’s not a typical story. I know that it should have been harder to stop this pattern of behavior, and I also know that it’s not especially helpful to say “I guess I just decided to stop having a serious disease.” But that’s also, of course, not exactly what happened. Whatever forces created my anorexia didn’t magically disappear; there are threads of them in my life still. I’m still hungry for control; I still place too much importance on external markers of validation. And, of course, there’s the fact that I just had a surgery to make myself feel more confident about my post-baby body. It seems to me extremely irresponsible to ignore the similarities between my decision to pursue breast augmentation and the anorexia I struggled with for years; both are rooted in a willingness to put one’s body through enormous ordeals in the pursuit of some societally-created idea of physical beauty, and both are rooted in centuries of expectations held over the heads of women. But this is something I gave a great deal of thought to, and I ultimately felt that (to me) they were very different indeed: one was about self love, and the other was very, very much about self-loathing.

Still, though: I think it’s fairly obvious that both my surgery and my anorexia were expressions of my desire for control. One came from a healthier place than the other, but at the base level they’re really not so different at all. My need for control is a living thing; it’s been coursing through my veins for as long as I can remember, and emerges to make itself known in ways that are constantly changing. I used to control the size of my body; now I micromanage every facet of my family’s life and hold on to the reins of my job with an iron fist. I’m shitty at delegating, and I live in daily terror of my career falling to pieces, leaving me at sea once again.

I am not Zen.

It’s no mystery to me where this overwhelming need for control came from: it was born when I realized that I wouldn’t be able to control the thing that frightens me most, the thing I want control over more than I want anything on this planet.

I want to stop the people I love from dying. And I can’t. And so I control what’s in front of me instead.

{ Monterey Bay with my daughter | 2016 }

You know the saying “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference?” I’m terrible at that. My anorexia is many years gone, subsumed by the counter-balancing forces of my desire to keep my mind and body healthy for myself, for my husband, and of course most of all for my children. But I can‘t accept the things that I cannot change; I’ve never been able to. I do, however, think that it helps to acknowledge that simple fact, and to try to remember that the point I’m at is far less important than the direction I’m pointed in.

* * *

Why write about this now? Because it’s a topic I’ve been dancing around for years, and I don’t feel like doing that anymore. For a long, long time, the memory of the person I’d been made me feel ashamed, and shame is a big part of what allowed my disorder to bloom in the first place. Look, I haven’t “beaten” anything; I’ve just found some perspective. And it’s perspective that I need to work at preserving, because the forces that work to combat it – from media to misogyny – are real, and they are insidious.

I guess I’m just really disinterested in continuing to pretend that massive swathes of my life didn’t happen because the memories are embarrassing. They’re not good memories; I’ll give you that. But they’re mine, and shame and secrecy help no one.

These are my memories. This is my story. And the more I can own that story – whatever scary and humiliating and uncomfortable things that ownership forces me to confront – the more I take back my power from those who try to strip me of it…including myself.