Raja Ampat, Indonesia

In No Is Not Enough – one of my favorite books, and one I think about often – the activist Naomi Klein describes taking her five-year-old to the Great Barrier Reef. She was there to study climate change and the related destruction of the reef, and thought a great deal about whether to show him the vast landscapes of barren, bleached coral. Her instinct was to impress upon him, even at that young age, just how much had been lost, and how much more could be lost still.

And yet she didn’t. She instead steered her child towards the most vibrant, beautiful corners of the reef, the parts still teeming with fish and coral and the kinds of colors you see only in dreams or on acid trips (or so I hear). Because how, she reasoned, can you fight for something if you don’t learn to love it first?

I’ve spent a great deal of time on this trip – which I will post about in the days to come in far more fun and lighthearted ways – talking about what we’ve borne witness to. The beauty of it. And the heartbreaking fragility.

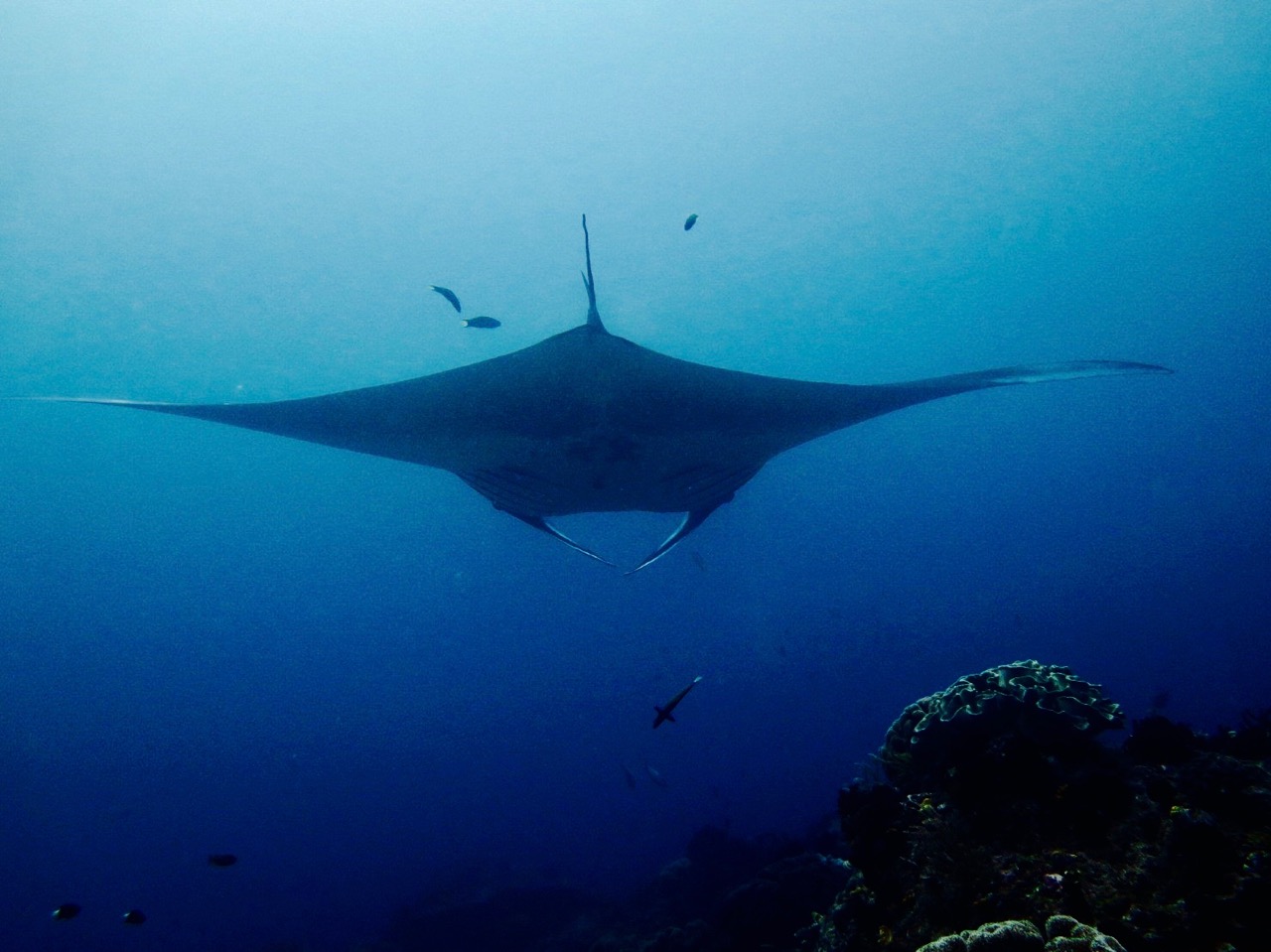

I swim past Napoleon Wrasses the size of doghouses, watch mantas grin at me as they fly past. Goodbye, I think as they swim away. I waggle my fingers at them, and wonder whether I will see them again one day. I wonder whether, by the time I allow my children to strap on a tank and descend into the depths, these smiling creatures will be gone.

I asked my friend Luke, a passionate conservationist with whom I’ve been having these chats these last few days – to write a bit on this topic. And so: here is Luke. He is British, and odd, and I think you will like him. I hope you hear what he has to say.

![]()

I am the one who is not in a dress.

by Luke

Hello, Ramshackle Glam. I am Luke. I am a 35-year-old English guy presently fulfilling a long-held dream of mine: I am, at this moment, aboard a boat skimming across the waves in Raja Ampat, in West Papua, Indonesia.

I am here to experience some of the best scuba diving on the planet.

I am also here, in a way, to pay homage to one our planet’s great submarine wildernesses. And maybe – though I hope not – I am here to say goodbye.

I hate goodbyes. They are shit, really. As a planet, we are in the process of bidding farewell to the Barrier Reef: Once the globe’s largest organism, visible even from space. Now it’s an ossified skeleton, the color and life leached out of it by rising ocean temperatures and increasing acidity.

On the first night of this trip, our merry gang drank more than a bit of Bintang beer and got to chatting. We are, the nine of us, on a glorious “live aboard” diving boat that looks something like an Asian pirate ship, were Asian pirates unexpectedly glamorous. The amazing Jordan and her epic dad Bob are here too, and thank god for small favors.

It’s the last day now, and the last dive is done. We’ve just returned to the wine-coloured surface of the sea, having spent the better part of the last hour drifting through the water alongside a trio of manta rays. You probably know what a stingray looks like from an aquarium or some such – so picture one of those, but truly gigantic, the length of a Tube carriage, say. (I am British. It’s like a subway car.)

These rays – oceanic mantas, the very largest kind – are graceful in a way that lends new meaning to the word. They are sea angels. They are transcendent; a prelapsian dream of perfect beauty. To watch them soar above you feels, quite simply, like looking straight into the eye of god. And they do look you in the eye. They see you. They play in your bubbles like puppies, begging you to tickle their white bellies as they fly between you and the surface, blocking out the sun.

I want to touch them as they pass overhead; of course I do. But the voice of our salty sea-dog of a dive guide rings in my mind: You mustn’t touch them, no matter how much you’re tempted. Touching them, you see – even as gently as you might stroke a baby, or a feather – can leave trails of bacteria on their soft skin, attracting parasites and perhaps harming them irreparably. Or even killing them.

Our dive guide is Dutch and quite wrinkly after 20 years soaking in the seawater, so I trust he knows his stuff. I do not touch my new friends.

As I float below the mantas, hands tucked safely across my chest, it strikes me how dangerous we are to these creatures; how unwittingly so. We want to touch them; to hold onto them; to bring them home with us in our words, and tell their stories again and again. We love them. Truly. And yet.

We take home our stories; so often, we leave behind ruin. Sunscreen, for example: Did you know that it’s a reef-killer? There are vast areas in the tropics that have banned sunblocks containing oxybenzene, because it creates a film on the surface of the ocean that prevents life-giving light from getting through to the creatures below. And – as we learned in seventh-grade biology and again (most critically) from The Lion King – there is, in fact, a circle of life, and it shatters as easily as fine crystal.

History has taught us that this is the fallacy of the mighty or fortunate: However good our intentions, the world does not exist to be ours.

Which reminds me: This morning, one of the mantas shat on my head. I guess I shouldn’t see this as a messianic anointment by nature – that would be in keeping with the aforementioned fallacy of the fortunate – but rather as a somewhat (but, if we’re being honest, not entirely) unpleasant coincidence. Truly, my head just happened to be near the manta’s butt as it swam by. It was a moment, though. Manta poop would probably sell quite well as conditioner in Whole Foods, I reckon.

So. As a species, how are we doing? It bears questioning: Are we getting better at extricating ourselves from our condescension? Taking action, rather than indulging in (hopefully unintentional, but also extremely unhelpful) self-congratulation because we used a paper straw, or plucked a plastic wrapper from the sea?

Slowly, perhaps.

Perhaps we are getting better, a small piece at a time.

I must believe it’s not all bad.

But still, we must remember – often, as often as we can – that as fortunate as we are, we are also responsible. Raja Ampat – home to our sweet manta friends, our funny wrasses, our graceful blacktips, our lovely damselfish, and our curious, retiring jawfish – can so easily go the way of those broken, underwater Australian wastelands we turn our children’s faces from, lest they be broken, too.

One day, though, these children will grow to women and men, and in their eyes our failings will be laid bare. It is my great hope that I am wrong; that what they see before them will be the smiling manta; the circling blacktip; the ocean heaving with pure life. And if it is not, well, then: god willing, they will take us by the hand, and together we will make right our grievous wrongs.